Day 157: Stickers

The first time I saw one of the bumper stickers for the fallen (memorial stickers? Is there even a proper name for them?) was during Lavi’s shloshim. At the end of the ceremony marking the thirty-day mourning period, Lavi’s 15-year-old cousin began cutting strips of four or five stickers from a roll of self-adhesive labels, then handing them out the dozens of friends and family gathered in the military cemetery. There were two versions to chose from, one in which Lavi had his olive green uniform, another in which he was wearing a black windbreaker, the blue sky in the background. One said “I enlisted for my country. My life is not worth more than anybody else’s life.” In the other, an exhortation to care for nature, for living beings, and to be in the service of others. “Do, Always. In memory of Sgt. Lavi Lipshitz Z”L.”

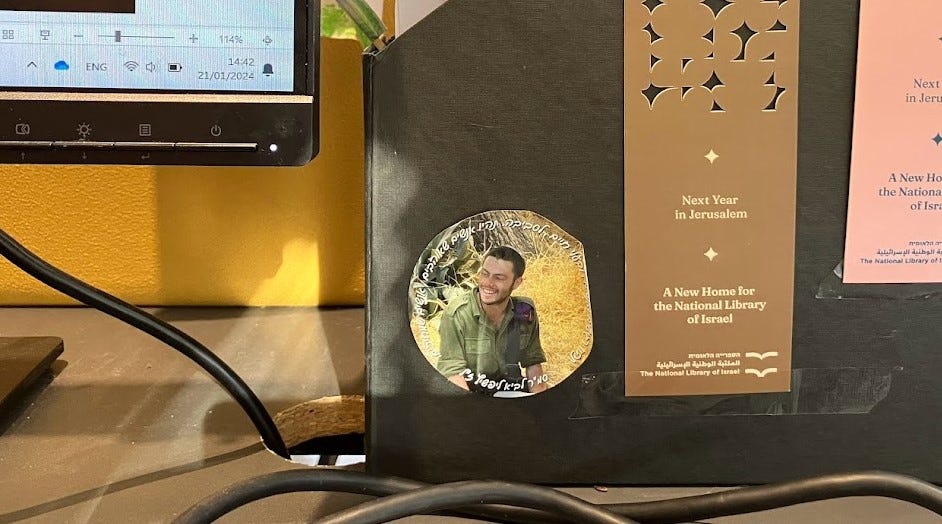

One of the memorial stickers for Lavi, which I keep on my desk at the office

That simple act moved me deeply. On one hand, it felt completely natural. But what could be more bizarre than teenage girl handing out stickers with the photo of the young man buried only a few meters behind you? My background in the print industry meant I was used to giving (or gathering) samples of printed materials at busy, noisy trade shows. But that late November morning, in the solemnity and silence of the cemetery, I was taken aback by how teens were using print to remember their Scouts counselor, their brother, their cousin, their close friend.

A couple of months ago, I began noticing memorial stickers everywhere. In bus stops. On windshields. On the decorative lamp in the waiting room of the dentist. Pasted on the concrete walls of the Kiriya, the main headquarters of the IDF in Tel Aviv. Most were memorializing soldiers whose names or photographs were often familiar, sometimes from the news, other times because they were friends or relatives of people I knew. Others had the names and portraits of victims of the October 7th massacres, including many of those murdered at the Nova Music Festival, whose names, for some reason, have not yet made it to our collective consciousness.

On a windshield in Modiin, last Saturday, in memory of Gili Hadar “the sun in our lives.”

At some point, I started taking photos of the stickers. I’m not sure what generated that impulse — getting to know each victim? Preserving content of the sticker, knowing that labels, especially those left outside in the sun and the rain, inevitably peel off, fade, scuff? Whatever the reason, I was bent on not missing a single one. And so, in early January, I began taking photos of each and every sticker I came across— while walking from the parking lot to the office, on a parked car near my house, outside the train station in Jerusalem, or in the pedestrian bridge above the Ayalon highway in Tel Aviv.

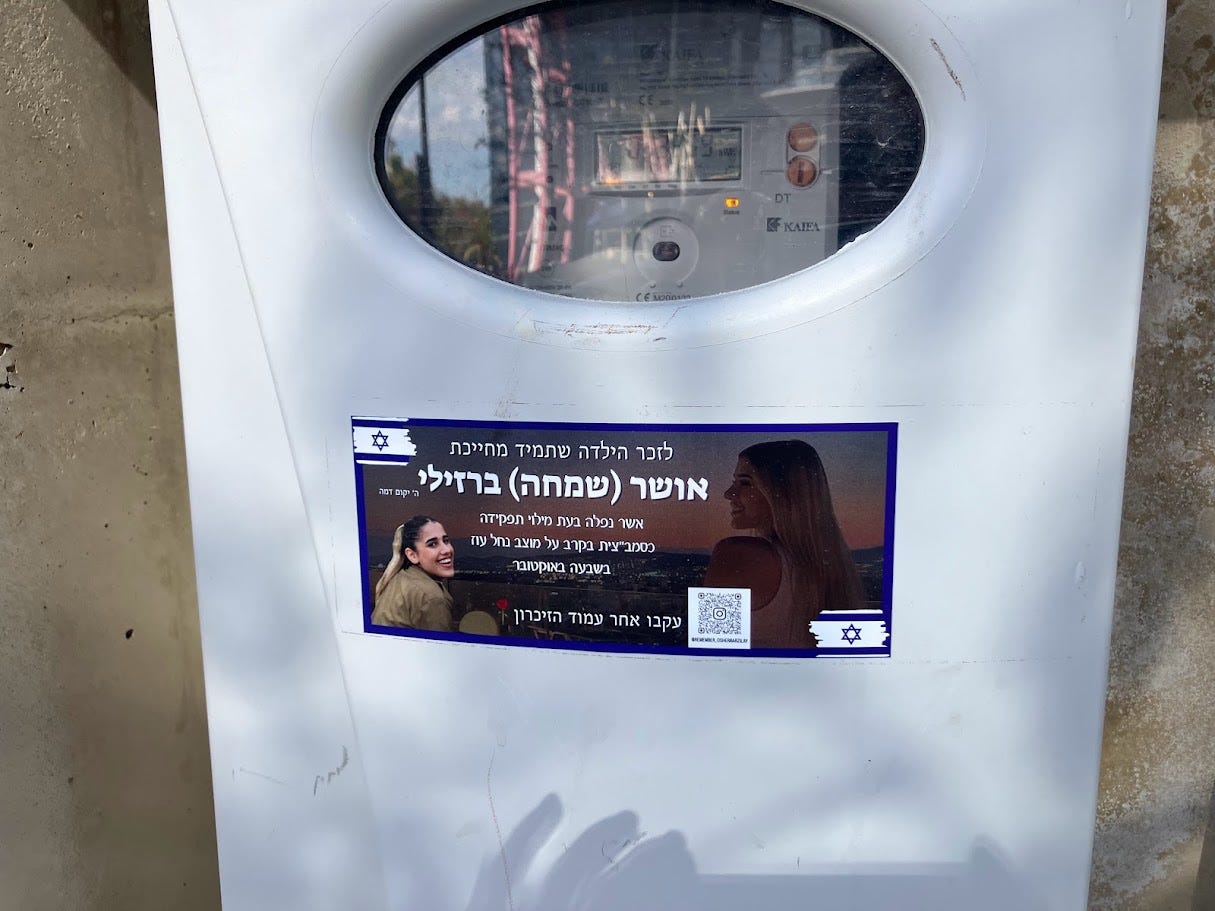

On an electrical box in Rehovot

On a pedestrian bridge over the Ayalon Highway in Tel Aviv

Next to a bus stop in central Modiin

Late last month, as I was unzipping my backpack for inspection at the entrance to the mall, one sticker made me stop on my tracks. It had a picture of Ori Shani Z”L, and in bold white letters, the words “Good will triumph! ”

I mentioned the sticker to Yishai, Ori’s brother, when we talked about the library he wants to dedicate to Ori. “Yes, that was me!” he said with a smile. When I asked him where the idea came from, he showed me a funny clip of Ori giving a spontaneous mock speech to the camera, which he finished with “good will triumph.” The mantra stuck. After Ori fell on October 7th, Yishai made the stickers, which he then gave to his kids to take to school and share with their friends.

The next time I went to the mall, I noticed there were two additional memorial stickers next to the one for Ori. It seems that these stickers don’t just serve as “mobile memorials” but as magnets for others to do the same.

Last week, I began creating an online photo album with all the stickers I’ve photographed so far. I was expected there would be thought there would be two dozen of them, but at last count, there were over 80 different stickers. (One caveat, these include stickers like, in Lavi’s case, have multiple versions to memorialize the same person.)

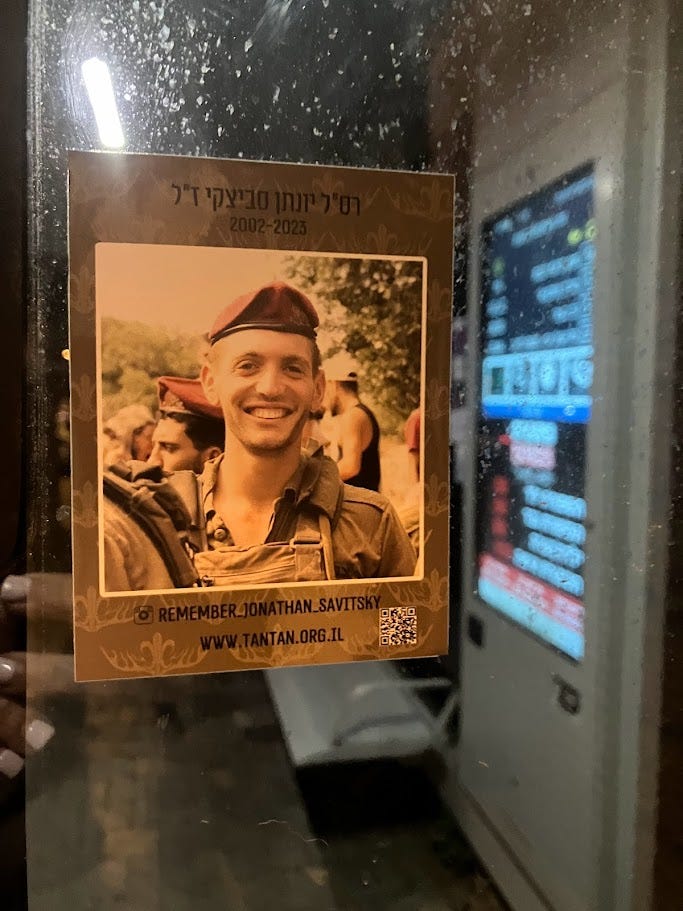

Two of my favorite are below. They are for Jonathan Savitsky Z”L, about whose shiva I wrote back on Day 10 of the war. I don’t want to describe these stickers in terms of design, or branding, of call to action, because it feels reductive. But in trying to understand what drew me to them, besides the fact that my son probably owes his life to him and to the rest of the soldiers to rushed to defend Kissufim on October 7th, is the simple fact that it feels inviting. Whoever made it wants you to visit the website, the Instagram page, and stay. To learn more about his family and his life. To see photos of him growing up. To read messages left by his friends.

On the home page (this is the English version,) one learns that the domain name of the website, Tantan, comes from the nickname his father used.

A sticker for Staff Sgt. Jonathan Savitsky, on a bus stop in Modiin last Saturday.

This morning I came across a second version of this sticker outside the Modiin Central train station. The text in Hebrew reads “We Remember You, Yonichka,” which the website also mentions, is what his mother used to call him.

Another sticker in memory of Staff Sgt. Jonathan Savitsky, spotted today in Modiin.

I thought about the rest of the nicknames on the home page of www.tantan.org.il: what his sister called him. What his girlfriend called him. What his friends called him. How many stickers are required to begin to know a person? How many websites, or books, or full-scale monuments are needed to properly commemorate a life lost?